Duplicating Spheres and the Banach-Tarski Paradox

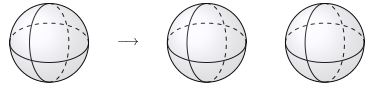

The Banach-Tarksi paradox is one of the most counterintuitive and astounding results in mathematics. Informally, it states that we may slice a sphere into finitely many pieces which can then be reassembled into two exact copies of the original sphere.

The paradox arises from the fact that we have doubled the volume of the sphere by rearranging pieces of it. In this post, we’ll resolve this paradox by closely examining our intuitive notion of volume. In addition, we’ll show why the paradox is true, at least in spirit. (The actual proof of this result has some fairly technical and boring parts; we will show the illuminating idea behind the proof.)

More formally, the Banach-Tarski paradox states that

if \(S\) and \(T\) are subsets of three-dimensional space (\(\mathbb{R}^3\)) with nonempty interior, then \(S\) may be sliced into finitely many pieces which may be rearranged into an exact copy of \(T\) using only isometries of \(\mathbb{R}^3\).

The hypothesis the that subsets have nonempty interior roughly corresponds to the fact that they must be honest-to-goodness three-dimensional solids. It excludes points, which are zero-dimensional, curves, which are one-dimensional, and surfaces, which are two-dimensional. An isometry of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) is a transformation which preserves the distance between points. Examples of transformations of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) are translations and rotations. As a consequence of preserving distances, isometries also preserve volume.

The Properties of Volume

For a subset \(S\) of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), let \(V(S)\) be the volume of \(S\). Even in this seemingly innocuous sentence, we have already come close to the heart of the Banach-Tarski paradox.

Does every subset of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) have a volume?

At first, this question seems perposterous. In fact, mathematicians did not give it serious consideration until the development of measure theory around the turn of the 20th century. The resolution of this question will lead to the resolution of the Banach-Tarski paradox. For now, however, we focus on the properties of volume whenever it is defined.

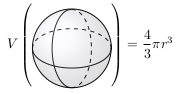

First, for \(V(\cdot)\) to correspond with our intuitive notion of volume, it should assign well-known solids their usual volumes. For example, if \(B_r\) is a sphere of radius \(r\), we expect that \(V(B_r) = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3\).

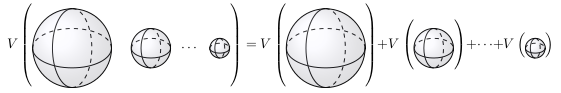

Second, if \(S\) and \(T\) are disjoint (nonoverlapping) subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), it seems reasonable that their volume together should be the sum of their volumes. That is, \(V(S \cup T) = V(S) + V(T)\).

We can generalize this property to finitely many pairwise disjoint sets \(S_1, \ldots, S_n\) as \(V(S_1 \cup \cdots \cup S_n) = V(S_1) + \cdots + V(S_n)\) using induction.

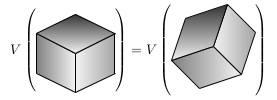

Third, moving or rotating a solid (but not stretching it) should not change its volume. More precisely, if \(T\) can be obtained from \(S\) by Euclidean isometries (translations, rotations, etc.), then \(V(S) = V(T)\).

We summarize these properties of volume here.

- Well-known solids are assigned the correct volume. If \(B_r\) is a sphere of radius \(r\), \(V(B_r) = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3\).

- If \(S_1, \ldots S_n\) are pairwise disjoint, \(V(S_1 \cup \cdots \cup S_n) = V(S_1) + \cdots + V(S_n)\).

- If \(T\) is obtained from \(S\) by Euclidean isometries, \(V(S) = V(T)\).

Some readers with mathematical experience may notice that \(V\) is a finitely additive measure.

Free Groups and Euclidean Isometries

We now turn our attention to the free group on two generators, which initially seems rather abstract and unrelated to the geometric Banach-Tarski paradox. At the end of this section and in the next section, however, we will show that the free group is intimately connected to the Banach-Tarski paradox.

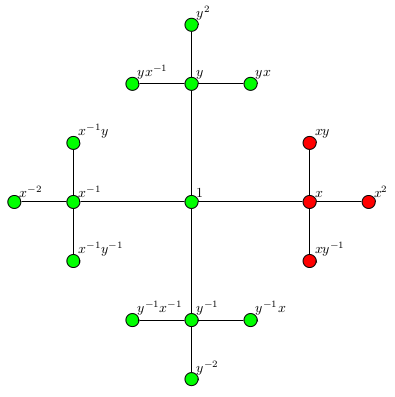

The free group on two generators, \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is defined as follows. Let \(x\) and \(y\) be two symbols, with formal inverses \(x^{-1}\) and \(y^{-1}\). (That is, \(x x^{-1} = 1 = x^{-1} x\), and \(y y^{-1} = 1 = y^{-1} y\).) The free group on two generators is \(\mathbb{F}_2 = \{\textrm{reduced words in } x, y, x^{-1}\textrm{, and } y^{-1}\}\).

A word in \(x\), \(y\), \(x^{-1}\), and \(y^{-1}\) is a sequence of these symbols. For example, \(x y\), \(x^2 y x^{-1}\), and \(y^{-1} x y y^{-2} x^{-1}\) are all words in these four symbols. (Here \(x^2 = x x\), etc.) A reduced word is one in which no symbol appears adjacent to its formal inverse. In any situation where these pairs occur consecutively, we may cancel the pair to produce a shorter word. Of our example words, the first two are reduced, while the third is not. We may reduce the third example as

\[y^{-1} x y y^{-2} x^{-1} = y^{-1} x (y y^{-1}) y^{-1} x^{-1} = y^{-1} x y^{-1} x^{-1},\]

which is now a reduced word.

We have now defined \(\mathbb{F}_2\) as a set, but it requires a product to become a group. For two reduced words \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) in \(\mathbb{F}_2\), their product \(w_1 w_2\) is formed by concatenating \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) and reducing the result. For example, if \(w_1 = y x y x^{-1}\) and \(w_2 = x y^{-1} x^2 y\), then the product is

\[w_1 w_2 = (y x y x^{-1}) (x y^{-1} x^2 y) = y x y y^{-1} x^2 y = y x^3 y.\]

We’ve managed to define the free group on two generators, but it seems rather abstract at this point. Fortunately, we are now in a position to connect \(\mathbb{F}_2\) to the Banach-Tarski paradox. The matrices

\[X = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{1}{3} & -\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3} & 0 \\ \frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3} & \frac{1}{3} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\]

and

\[Y = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{3} & -\frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3} \\ 0 & \frac{2 \sqrt{2}}{3} & \frac{1}{3} \end{pmatrix}\]

represent rotations of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). It can be shown that \(X\) and \(Y\) generate a copy of the free group, \(\mathbb{F}_2\), inside the group of isometries of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). (To do so, one must show that no reduced word in \(X\) and \(Y\) can act as the identity on \(\mathbb{R}^3\).)

The Nonamenability of the Free Group

Since the free group on two generators is present in the isometries of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), we may define a volume-like function on the free group, with properties corresponding to those of volume almost exactly. Whether or not such a volume-like function exists on \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is the key to understanding the source of the Banach-Tarski paradox.

A mean is a function \(m\) that maps subsets of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) to the unit interval \([0, 1]\) with the following properties.

- \(m(\mathbb{F}_2) = 1\)

- For \(S_1, \ldots, S_n \subseteq \mathbb{F}_2\) which are pairwise disjoint, \(m(S_1 \cup \cdots \cup S_n) = m(S_1) + \cdots + m(S_n)\).

- For \(S \subseteq \mathbb{F}_2\) and \(w \in \mathbb{F_2}\), \(m(w S) = m(S)\).

If such a mean exists, \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is called amenable. Intuitively, the mean of a subset of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) quantifies what proportion of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) the subset occupies. With this interpretation, the three properties of a mean correpsond closely to the three properties of volume listed earlier. It seems reasonable that \(\mathbb{F}_2\) should occupy 100% of itself, so property (1) of \(m\) corresponds to property (1) of volume. Property (2) of \(m\) and property (2) of volume are so similar that any further comment seems unnecessary. Property (3) of \(m\) merits further discussion. The set \(w S = \{w s | s \in S\}\) corresponds to a translation of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). In fact, since left multiplication of a subsets of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) by a fixed element of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is a bijection, the map \(S \mapsto w S\) can be considered an “isometry” of \(\mathbb{F}_2\). Property (3) of \(m\) then states that “isometries” should not change the proportional size of a subset, which corresponds to property (3) of volume.

We will now show that \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is not amenable. To do so, we must consider the Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\).

They Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is a geometric representation of the group. We will illustrate a decomposition and rearrangement of the Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) that gives rise to the Banach-Tarski paradox. This decomposition will show that \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is not amenable.

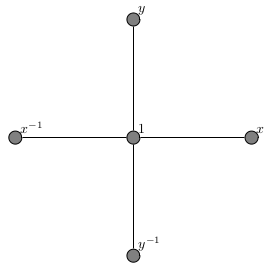

To form the Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\), we begin by connecting vertices for each of the four generators \(x\), \(y\), \(x^{-1}\), and \(y^{-1}\) to a vertex corresponding to the identity element.

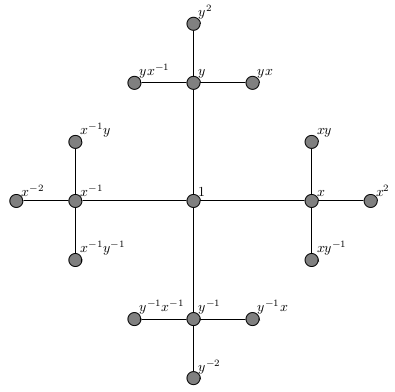

To each of these four vertices, we attach three new vertices, correpsonding to multiplication on the right by \(x\), \(y\), \(x^{-1}\), and \(y^{-1}\). Note that this only produces three new vertices (at each existing vertex), since multiplication by the vertex’s inverse element returns us to the vertex corresponding to \(1\).

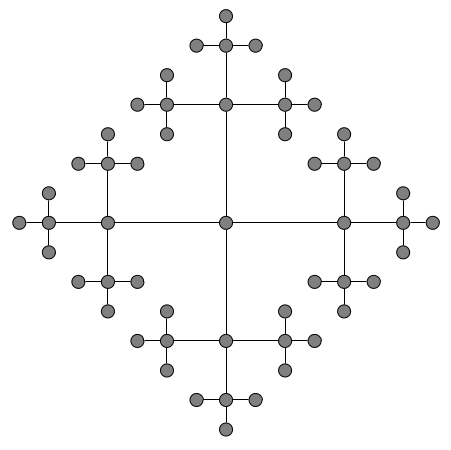

Repeating this procedure at each of the new vertices, we arrive at the following graph. (Vertex labels have been removed due to the increased density of the vertices.)

Repeating this process ad infinitum, we arrive at the Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\), which is a four-regular tree. The power of this Cayley graph is that it provides a geometric lens through which we may view \(\mathbb{F}_2\). If \(w\) and \(w'\) are two reduced words in \(\mathbb{F}_2\), we can define the distance between \(w\) and \(w'\) as the number of edges in the shortest path connecting their vertices in the Cayley graph of \(\mathbb{F}_2\). Once we define the distance between elements of \(\mathbb{F}_2\), we can study the geometry of \(\mathbb{F}_2\). This idea leads to the deep and fascinating field of geometric group theory.

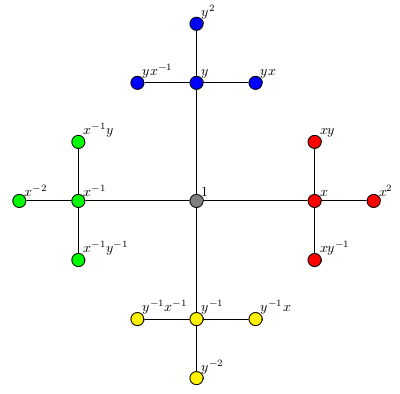

We now have all of the tools necessary to show that \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is not amenable, the fact that underlies the Banach-Tarski paradox. Let \(W(x)\) be the set of all reduced words in \(\mathbb{F}_2\) that being with \(x\). Define \(W(y)\), \(W(x^{-1})\), and \(W(y^{-1})\) similarly.

Above we have colored \(W(x)\) in red, \(W(y)\) in blue, \(W(x^{-1})\) in green and \(W(y^{-1})\) in yellow. This diagram illustrates the decomposition

\[\mathbb{F}_2 = \{1\} \cup W(x) \cup W(y) \cup W(x^{-1}) \cup W(y^{-1}).\]

The nonamenability of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) (and consequently the Banach-Tarski paradox) arises from another decomposition of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) which contradicts the one above. The key to the second decomposition is calculating the complement of \(W(x)\). If \(w\) is not in \(W(x)\), then \(x^{-1} w\) is in \(W(x^{-1})\) (since there is no initial \(x\) to cancel), so \(w = x (x^{-1} w)\) is an element of \(x W(x^{-1})\). Similarly, if \(w'\) is in \(x W(x^{-1})\), then it cannot start with \(x\), so \(W(x)^\mathsf{c} = x W(x^{-1})\). The second decomposition of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is then

\[\mathbb{F}_2 = W(x) \cup W(x)^\mathsf{c} = W(x) \cup x W(x^{-1}).\]

This decomposition is shown in the following diagram.

Here \(W(x)\) is shown in red, and \(x W(x^{-1})\) is shown in green. The fact that the multiplying \(W(x^{-1})\) by \(x\) (which corresponds to a translation of \(\mathbb{R}^3\)) causes the set of green vertices in the first decomposition to absorb the blue, yellow, and gray vertices leads to the nonamenability of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) and the Banach-Tarski paradox.

Now we’ll show formally that these two decompositions cause \(\mathbb{F}_2\) to be nonamenable. The proof proceeds by contradiction. Suppose \(m\) is a mean on \(\mathbb{F}_2\). From the second decomposition,

\[\begin{align*} m(\mathbb{F}_2) & = m(W(x)) + m(x W(x^{-1})) \\ 1 & = m(W(x)) + m(W(x^{-1})). \end{align*}\]

In this calculation, the first equality follows from property (2) of \(m\) and the second equality follows from properties (1) and (3) of \(m\). We can also produce a third decomposition of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) as \(\mathbb{F}_2 = W(y) \cup y W(y^{-1}),\) so a similar argument shows that \(1 = m(W(y)) + m(W(y^{-1}))\). Combining these two facts with the first decomposition, we get

\[\begin{align*} m(\mathbb{F}_2) & = m(\{1\}) + m(W(x)) + m(W(y)) + m(W(x^{-1})) + m(W(y^{-1})) \\ m(\mathbb{F}_2) & \geq m(W(x))+ m(W(x^{-1})) + m(W(y)) + m(W(y^{-1})) \\ 1 & \geq 1 + 1 = 2, \end{align*}\]

which is a contradiction. The second step of this derivation comes from dropping the terms \(m(\{1\})\) from the right hand side, which must be nonnegative, since the range of \(m\) is \([0, 1]\).

Due to the prescence of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) in the group of isometries of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), we can transfer these decompositions of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) to \(\mathbb{R}^3\), leading to the Banach-Tarski paradox. The transition to \(\mathbb{R}^3\) involves a technical argument that requires a bit of care. For details see Chapter 0 of Volker Runde’s excellent book Lectures on Amenability1. It is worth nothing that this argument involves the axiom of choice, so that while we gave an explicit description of conflicting decompositions of \(\mathbb{F}_2\), we are only able to prove that such a decompositions exist in \(\mathbb{F}_2\), not describe it explicitly.

Resolving the Paradox

When considering the properties of volume, we arrived at the question of whether or not every subset of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) can be assigned a volume. Fortunately for mathematicians, the answer is no. The fact that \(\mathbb{F}_2\) is nonamenable intuitively means that it is impossible to say what proportion of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) every subset occupies in a consistent manner. Through the presence of \(\mathbb{F}_2\) in the isometries of \(\mathbb{R}^3\), this leads to the impossibility of assigning a volume to every subset of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). (There are much more succint proofs that \(\mathbb{R}^3\) contains nonmeasurable subsets; we chose to take a longer route to this fact in order to show the origin of the Banach-Tarski paradox.)

The Banach-Tarski paradox is resolved by noting that as long as at least one of the slices of the original sphere does not have a volume, the notion of doubling its volume is meaningless.

Runde, Volker. Lectures on amenability. No. 1774. Springer, 2002.↩︎